Last Updated on January 22, 2023

I never used to run random encounters in my games.

I had about two hours each week to play D&D; I’d written some “plot,” and I’d be damned if I wasn’t going to railroad my players through it before we all got too sleepy or drunk to remember what was going on.

In the years since, however, I’ve come to love random encounters.

Used correctly, they breathe life into your worlds and make the wilderness feel dangerous, and they are actually a tool for creating and advancing stories rather than getting in the way of the things you already had planned.

Welcome to our guide to running random encounters and wandering monsters for D&D 5e dungeon masters.

We’re going to go over why you should be running random encounters, what you can use them to achieve, when you should be rolling for them, where you can find premade ones, and how to build your own.

What Are Random Encounters?

A random encounter is any encounter that’s not part of a predetermined “plot.”

Whether that means a goblin ambush or spotting a ruined tower in the distance, random encounters (and wandering monsters) are a great way to make your world feel dangerous, enticing, and alive.

Let’s get started.

Why Use a Random Encounter?

There’s a mixture of reasons in the Dungeon Master’s Guide for using random encounters that range from “drain character resources” to creating “urgency.”

For the most part, I agree with the sentiments expressed, but I think it does a pretty bad job of explaining why random encounters are a good thing.

To be fair, there is an entry on using random encounters to reinforce the theme of a campaign – vampire bats and wolves for horror, wounded soldiers for a land gripped by war – which is great advice.

However, the way it’s worded (focusing on using random encounters to support a central narrative or storytelling objective) illustrates why random encounters don’t feel at home in 5e.

5e’s adventure design philosophy is geared towards narrative adventures and treats random encounters as a sort of inconvenient holdout from the days when D&D was more about going into dungeons and poking things with sticks just because something cool might happen.

“Not every DM likes to use random encounters. You might find that they distract from your game or are otherwise causing more trouble than you want. If random encounters don’t work for you, don’t use them.”

– Dungeon Master’s Guide

You can totally use random encounters in this very “all must serve the plot” kind of way, but I think there’s a way of looking at them that encompasses both that attitude and does so much more.

I use random encounters for three reasons: Make the World Feel Dangerous, Make the World Feel Alive, and Put New Content in Front of the Players.

Sometimes an encounter serves one; other times it can fulfill two or all three of those goals.

Make Your World Feel Dangerous

It’s generally assumed that D&D takes place in a world where civilization exists as flickering points of light in a vast, dangerous expanse of wilderness.

Here, there be a tavern and some shops. Out there? There be monsters out there. And dungeons. (And dragons.) And treasure if you’re lucky.

I get into this wilderness/civilization dichotomy more in this article about overland travel, but the essence is that, when your players step out of town, they step into the wilderness. And the wilderness is a scary place.

Random encounters are the best way to reinforce the fact that a simple trek through the woods always has the chance to vomit forth something big, dangerous, and hungry.

There are dragons and trolls and owlbears and goblins and – You get the idea. There’s bad stuff out here.

What’s the Difference Between a Random Encounter and a Wandering Monster?

Functionally, there’s no strict difference. It’s more contextual – tied up in translation between different editions of the game.

A good way to think about it, however, is that Wandering Monsters are something that can crop up when the players explore dungeons or otherwise dangerous, self-contained areas and – at least this is how they used to work – happen in a more structured way.

They’re tied to the old D&D idea that time outside of combat was measured in roughly 10 minute “turns.”

Doing a “thing,” like picking a lock, searching for traps, walking down a corridor with your trusty ten-foot pole in hand, was all assumed to take “one turn.”

Every few turns, things happened: spells ran out or torches needed replacing, and every two turns, the DM would roll a d6 to see if any wandering monsters showed up.

Personally, I like the way this creates a constant trade-off between the players moving carefully, exploring everything they want to explore, and the increasing risk of a wandering monster.

A random encounter, on the other hand, is something that’s broader in scope (a social encounter, a new location, something cool off in the distance, or a wandering monster) that happens less frequently outside the dungeon.

A DM might only roll for a random encounter once or twice a day, whereas in the dungeon they would roll for wandering monsters every 20-ish minutes.

Using random encounters makes the wilderness feel unpredictable, dangerous; they remind the players that they might be the heroes of their own story, but the infinite, untamable wilderness couldn’t give a giant rat’s ass.

This philosophy doesn’t just apply to the wilderness.

Any space you want to feel large and dangerous benefits from a random encounter table, whether it’s the planes of Avernus or a sprawling city full of pickpockets, cultists, and people handing out fliers about pickpocket insurance.

Make Your World Feel Alive

I’m about to hit you with my most important piece of DM wisdom right here: our job, more than being storytellers and voice actors, more than picking music and running combat, is to create verisimilitude.

Everything I do as a dungeon master is at least in part done to make my world feel like it’s alive.

If I can do that and convince my players not to think of my world as a video game or a story that’s all about them but, rather, a living, breathing world that existed before they arrived and will continue to exist when they’re gone, then I think I’m doing my job.

One of the best ways to do this, in my opinion, is to limit my own agency as the alpha, omega, author – what have you – of my world.

By giving up some say over what happens, when, and where, I let my world take on a life of its own.

Random encounters not only make your world feel dangerous but vibrant, alive, capable of the unexpected. It’s more fun for me, too.

Use random encounters to create little slice of life moments:

- You come across a trio of goblins fighting over a very big fish.

- A young man bursts through the foliage, eyes wild, shouting “Where is it?! Did you see which way it went?!”

- A trio of surly dwarves in black armor stand around, smoking pipes as they watch a tearful halfling dig a shallow grave. The dwarves are having an involved conversation about something called “Baked Ziti.”

Your players are under no obligation to engage with these random encounters (even if the encounters sometimes want to engage with the players).

Whether they jump in feet first or march past without a second glance, you’re reinforcing the idea that there’s stuff happening in the world that has nothing to do with the party.

It’s happening everywhere. All the time. The world is alive. It’s Aliiiiveee!!!

Random Encounters Don’t Have to Mean Interaction

Just because someone rolled a random encounter doesn’t mean you need to start gearing up for a combat, or come up with a new NPC voice, or even give the players anything to do.

A great trick I picked up (I think I encountered it first on Matt Colville’s campaign diaries for the Chain of Acheron – where a PC stood on the deck of a ship and watched an unfathomably large whale swim past the bow) is that “random encounter” doesn’t always have to equal “something to do.”

Sometimes, just giving your players something to look at, hear, or smell is enough to make your world feel big.

Think of the scene in the Fellowship of the Ring when the party passes upriver through the Passage of Kings. They don’t do anything.

The “DM” just describes two absolutely massive, ancient statues that speak to the unfathomable grandeur of ages past and just how long ago those elder days were.

Some ideas for non-interaction random encounters include:

- A procession of pilgrims, voices raised in song, bearing a high priestess clad all in gold upon an ornate bower.

- Something big, flying impossibly high overhead – its scale only hinted at by the shadow it casts for a second upon a distant mountain peak.

- Nestled in a clearing, a small henge made from chunks of rose-colored crystal, gently reflecting and refracting the afternoon sun into dizzying geometric patterns.

Obviously, if your players decide to go talk to the pilgrims, track the dragon, or start poking the weird crystals, stuff is gonna happen, but most of the time, players will be content to sit back and enjoy the show.

Further Reading:

Put New Content in Front of Your Players

Lastly, random encounters are a great way to introduce new content, side quests, and plot hooks or even put elements of the main storyline in front of your players.

For example (stop reading now, Scott, I’m talking about our weekly game), in a campaign I’m running at the moment, the party rolled a random encounter last week and got jumped by a gang of hobgoblins.

This could have been a simple speed bump between town and the dungeon.

Instead, the hobgoblins specifically tried to take the party’s magic users alive, only targeting the rest with lethal attacks. This was a kidnapping rather than a simple robbery.

When looting the bodies, the parties found some strange gems (“deep opals, found only in the most deepest dwarven mines”) on the leader’s person, along with a strange document appearing to be a bill of sale, signed by the hobgoblin boss and someone else in shimmering black ink.

Soon, they’ll hear other stories of these monsters attacking travelers on the roads, dragging away magic users and leaving everyone else dead.

They’ll start to wonder why this is happening. If they want to know more, they’ll have to start doing some investigating on their own.

Just like that, you can turn a simple random encounter (you’re ambushed by 2d6 hobgoblins) into the groundwork for a whole new adventure (astute readers will smell the foul odor of 2e’s Night Below, which I’m adapting as a possible next stage for this campaign).

My point is that new adventures and new content don’t always have to arrive neatly at the end of the previous adventure – delivered by a mysterious figure in a hooded robe at the end of the bar.

You can start hinting at the next adventure(s) in the middle of the current one using random encounters.

Again, this makes the world feel more alive, like the next set of bad guys aren’t waiting patiently for the party to wrap up whatever it is they’re currently doing.

Also, content doesn’t have to mean the next major arc of an adventure. Think of random encounters as a way to introduce B-plots and C-plots to a campaign.

Maybe there’s a union dispute going on at the local mine, or perhaps the local goblins are getting into a turf war with the orcs in the next valley.

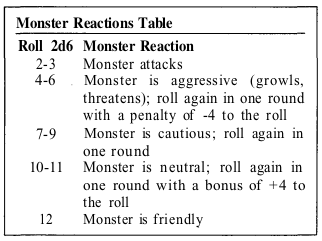

Use Reaction Rolls

I know, I know, most of my advice boils down to “steal this cool thing from old school D&D,” but hear me out.

Back in the old days, when your players bumped into a monster or NPC for the first time, it wasn’t completely up to the DM to decide how the creatures reacted.

They rolled 2d6 plus the lead player’s Charisma modifier, and the result determined how the monster reacted to the party.

Check out this example:

Personally, I love any mechanic that takes the pressure off me to be the arbiter of every little thing that happens to the party.

Eroding the assumption that enemies are either immediately friendly or mindlessly attack once again (all together now) breathes more life into your world.

Remember, random encounters don’t always have to happen to the players.

Simply having them stumble into someone else’s story is going to both provide an opportunity for more adventuring and continue to reinforce the impression that your world is a living, breathing place.

When Do I Roll For a Random Encounter?

In D&D 5e, the official recommendations for when to roll for a random encounter are when:

- The players are getting off track and slowing down the game.

- The characters stop for a short or long rest.

- The characters are undertaking a long, uneventful journey.

- The characters draw attention to themselves when they should be keeping a low profile.

This is pretty okay advice, although I don’t love the idea that random encounters are supposed to be used to punish a distracted party (Do more plot or I swear I’ll get the Owlbear out again!).

If you’re not going to adopt the concept of “turns” from earlier editions, just using the above criteria is a pretty decent guide, although you can make up your own, more structured criteria if you wish.

Some ways to determine when to roll for a random encounter that I’ve heard before include:

- Whenever the players enter a new Hex.

- Twice per session of gameplay.

- Once per day.

- Whenever the game’s scene changes.

One way I like to handle rolling for a random encounter is to roll for the actual content ahead of time.

I’ll roll 2-3 times and make some notes on the results so I don’t get totally thrown.

Then, whenever it comes time to actually roll in game, I have one of the players roll for me. If they roll badly, one of the pre-generated encounters is triggered.

How To Roll For a Random Encounter

In 5e, to determine if a random encounter happens or not, the DM rolls a d20, with an encounter being triggered on a result of 18-20. This more or less recreates the old X-in-6 rolls from earlier D&D.

However, I prefer to use a d6 for an encounter (you can use whatever makes you happy; I know Matt Colville uses a d12 with an encounter on a 10+) because you can up the odds according to the environment:

Towns, Cities, and Farmland: 1-in-6

Forrests, Hills, Moorland: 2-in-6

Swamp, Mountains, Ruins: 3-in-6

And so on…

Into the Odd: Hint at Your Encounters

The excellent, rules-lite industrial horror game Into the Odd has a great approach to random encounters. It uses the basic 1-in-6 approach with a twist.

- On a 1, an encounter is triggered.

- On a 2, the players get a hint at an encounter nearby. They hear the sounds of footsteps from further down the passage, find the poorly-hidden signs of an orc camp, smell the smoke from a goblin cooking fire, and see a dragon soaring through the sky far above.

This approach gives your players the choice (on a 2) whether they want to interact with the encounter or try to get out of its way.

How To Create A Random Encounter Table

If you want to just grab an existing random encounter table and start rolling, there are thousands of options available online, in both official and community sources – not to mention generators.

Xanathar’s Guide to Everything has an amazing, expansive list of d100 random encounter tables arranged by both terrain and character level.

These are pretty par for the course in terms of quality, and they contain some fantastically evocative entries like:

A beached whale, dead and bloated. If it takes any damage, it explodes, and each creature within 30 feet of it must make a DC 15 Dexterity saving throw, taking 5d6 bludgeoning damage on a failed save, or half as much damage on a successful one.

As well as some great visual encounters the players don’t have to interact with, like battling galleons out to sea, the majority of entries are about as extensive as “1d6 skeletons” or “1 frost giant” with no further explanation and the presumption, I think, that it’s going to be a fight.

This brings me to my first big tip if you want to make your own random encounters, which I think I’m stealing from an article in Knock! Issue #2.

What Are the Monsters Doing?

Populate your random encounter tables with monsters, but make sure you include a little seed, a little action. Say what the monsters are doing.

Rolling “1 ogre” is a lot less helpful as a DM trying to improvise than “1 ogre, fastidiously arranging his collection of severed heads on spikes outside his cave.”

With an extra sentence of description, you’ve already got a scene from which to work.

Does the ogre want more heads for its collection?

Probably, but I find the more life you can breathe into a scene, the less likely it is that the players will automatically assume they’re about to have a meaningless, resource-draining combat.

Populating a Random Encounter Table

If we take into account the three reasons why we might want an encounter to occur – Make the World Dangerous, Make the World Feel Alive, and Put Content in front of the Players – all we need to do is tailor a mixture of those three encounter types to the area in which your players are adventuring.

This is a great time to look at the local environment. Think about its flora and fauna, the side quests you’ve been meaning to introduce but haven’t figured out how, its history, and its factions, and smash all that into the table.

You also don’t have to pull a Xanathar’s and put 100 entries into every table. Using a d100 roll is mostly useful if you want to make some events less likely than others.

Goblin raiders might happen from 30-55, but the red dragon fight is only going to happen on a 99.

Otherwise, just use as many as you want and tweak things as you go. A few good encounters is better than 100 permutations of “1d6 Flumphs.”

To help give you an idea of how a random encounter table might shape up using these factors and the guidelines discussed above, I’ve put together an example.

Example Random Encounter Table: The Flanks of Firepeak Mountain

This is an encounter table for an area surrounding a volcano.

There’s a red dragon that lives in the volcano, a village of halflings living in its shadow that’s being overtaken by a cult of Tiamat, and the earthquakes caused by the dragon expanding its lair have started to stir up the undead who were sacrificed to the volcano centuries ago by a totally different cult.

Roll 1d8.

- The Red Dragon, soaring from its mountain lair to patrol its domain.

- A Procession of 3d6 Cultists make their way up the mountain from town, carrying a struggling non-believer between them, heading for a sacrificial stake outside the dragon’s lair.

- A loud rumbling from deep within the earth. Far above, the mountaintop belches inky smoke and streaks of fire into the sky.

- A crack in the ground with an Ogre Skeleton trapped in it, half-in-half-out of the red stone. A heavy golden chain engraved with dragonscale patterns (worth 250 gp) hangs around its neck. It has a very big club.

- A party of 1d4 + 1 terrified Halflings crouches among some rocks. They are on their way to try and rescue their brother who was taken up the mountain two days ago by the cultists, but they’re too scared of the dragon to continue.

- A distant, discordant screaming from deep beneath the earth – the song of a banshee trapped in a lava cave.

- Flickering ghosts. 2d6 pale, ghostly figures flee past you down the mountain, screaming before bursting into pale green flames.

- A Cave Mouth, recently opened by the earthquakes, gapes up at the sky. Inside, a winding, serpentine passage to the dragon’s lair and 1d4 Fire Snakes, freshly hatched.

- About Author

- Latest Posts

I played my first tabletop RPG (Pathfinder 1e, specifically) in college. I rocked up late to the first session with an unread rulebook and a human bard called Nick Jugger. It was a rocky start but I had a blast and now, the better part of a decade later, I play, write, and write about tabletop RPGs (mostly 5e, but also PBtA, Forged in the Dark and OSR) games for a living, which is wild.