Last Updated on January 22, 2023

Puzzles and traps have been an iconic part of Dungeons & Dragons since the earliest days of the game.

From tripwires and pressure plates that trigger swinging blades, volleys of poison darts, and sudden plunges into spike pits, to arcane logic puzzles involving inscrutable runes, different colored gems, and a magical circle of fire, there’s something about a good trap or puzzle that feels quintessentially D&D.

That being said, I don’t think D&D’s designers – from the earliest days of OD&D right the way up to 5e – ever actually figured out how to write rules that make traps fun, which in turn has led to traps being sort of… ignored.

In this article, we’ll be taking a look at how D&D 5e (as well as the editions that came before it) approaches traps, as well as how some of the rules’ shortcomings can be overcome with a few tips for running and making exciting scary trap-based encounters.

Up until very recently, D&D also tended to be pretty silent on the subject of puzzles. However, Tasha’s Cauldron of Everything introduces some official rules for puzzles, so we’ll take a look at them as well, and try to figure out why the advice offered in that book is so poorly represented by the examples in that very same book.

Then, we’ll present our top tips for running and making puzzles and traps, and follow them up with a whole heap of ready-made examples you can pick up and plug straight into any dungeon, cursed temple, or villain’s mountain lair that you choose.

You can use the contents drop down to jump straight into the example traps or to any section. Otherwise, let’s go.

Traps, Puzzles, and Golden Idols – an Introduction to the “Fourth Pillar of D&D”

Let’s look at what is hands down the best trap and puzzle-based dungeon in all of cinema, the temple of the golden idol from the opening sequence of India Jones: Raiders of the Lost Ark.

This is a fantastic sequence involving three traps and a puzzle, followed of course by the classic rolling boulder. I could do a whole other article on why this sequence is a masterclass in dungeon design, from the fiendish traps and atmospheric spiders to the way the dungeon creates challenges to getting both in and out again.

But I digress.

Indie and his last remaining guide Satipo walk down a dark, foreboding tunnel. Ahead, a beam of light pierces the darkness, perhaps hinting at a way forward. Indie holds out his hand.

“Stop. Stay out of the light.”

Indie has to deal with three traps and a puzzle in order to get his hands on the golden idol.

There’s the wall of spikes triggered by anyone disturbing a shaft of light, a good old-fashioned pit that’s too wide to jump, and a seemingly innocuous room dotted with pressure plates that trigger poisoned arrow traps.

Satipo: “Let us hurry. There is nothing to fear here.”

Indie: “That’s what scares me.”

Once Indie has bested these problems, he’s face to face with the treasure- I mean, uh, item of great archeological significance in all its glory.

This too is a trap of sorts, as the pedestal on which the idol rests is rigged to destroy the temple if it detects any change in weight.

However, because there’s an element of risk-reward in the immediate sense of Indie getting his hands on treasure, as opposed to a trap that needs to be bypassed or survived in order to get somewhere else, I would contend that the pedestal is actually a dangerous puzzle.

The temple of the golden idol is one of the most iconic trap dungeons in all of pop culture, not least because of its gripping conclusion: the steadily closing stone door and the rolling boulder.

So, if we take the light chamber, pit trap, poison darts, weighted pedestal, and door/rolling boulder elements in sequence, I think they’ll provide an excellent vehicle for understanding why traps and puzzles in D&D could be better, and how you can improve upon the rules as written (RAW) in your own games.

The Problem with Traps in the RAW

The rules for traps found in the Dungeon Master’s Guide are part common sense explanation, part infuriatingly vague. To paraphrase, traps can be found in many places and do many things.

Usually, they inflict damage that ranges from inconvenient to deadly, but some of them do other things too. They are usually triggered when someone goes somewhere, does or touches something, and can be magical or non-magical.

Sometimes, triggering a trap is simple, and sometimes it’s more complicated. You can find traps by making skills checks like Perception, Arcana, or Investigation, or by using a spell, and disarm them by making another check (adding your proficiency bonus if you have thieves’ tools).

And that’s about it. The RAW kind of shrug their shoulders and pass the buck along to the adventure and the DM. “In most cases, a trap’s description is clear enough that you can adjudicate whether a character’s actions locate or foil the trap,” reads the entry in the Dungeon Master’s Guide.

While that’s a little unsatisfying, you’re probably thinking “great! I’ll just follow the guidelines in the adventure I’m running or steal traps from an adventure to populate my own campaign.”

Well, individual traps in official 5e adventures don’t actually tend to give you much more to work with. Typically, a trap will set a DC to notice the trap, a DC to disarm the trap, and an amount of damage to inflict if the trap is triggered, as well as some suggestions for skills your players can use to make those checks or saves.

Let’s go back to the temple of the golden idol for a second and look at the light chamber with the spike wall. The DM (or George Lucas and Lawrence Kasdan, who wrote the original script) describes the following…

The adventurers “reach an arch in the hall. The small chamber ahead, which interrupts the hall, is brightly lit by a shaft of sunlight from high above.” Indie gets to a safe place and carefully disturbs the shaft of light, safely triggering the trap.

Now, if we were to represent that using the RAW, the party proceeds down the tunnel and the DM describes the scene. The DM calls for a Perception check as the party moves forward and, if one or more players pass, tells them there’s a trap there.

Indie’s player then passes a successful Investigation check and triggers the trap safely. No one takes any damage.

If the players failed their Perception check, the DM would have called for a Dexterity saving throw as the spiked wall rushed towards them. If they failed that save, then the trap would have inflicted some damage (probably just 1d8 piercing; it’s pretty early in the movie, after all).

Either way, everyone continues on into the next room. To me, as both a player and a DM, this is profoundly unsatisfying.

Whether or not my character takes damage is determined by two rolls which feel more or less arbitrary, and because we’ve only just walked inside the dungeon that our DM spent all weekend designing, they’re not going to kill me with a simple spike trap. So, what were the stakes? What was the point?

Traps in D&D 5e often feel like a tax. Every once in a while you roll a d20 apropo of very little and, if you roll badly, you lose some hp. And that’s it.

I think we can do better. But first, let’s talk about puzzles, why they’re different from traps, and how they’re officially presented in Tasha’s Cauldron of Everything.

Tasha’s Cauldron of Puzzles

The new rules introduced for puzzles in Tasha’s Cauldron of Everything start out so strong, but the book declines to follow its own advice when it comes to applying it to the puzzles it actually hands out to DMs.

“Why create a solvable puzzle? Just pose an enigmatic question without an answer and watch your trespassers squirm!” – Tasha

That’s honestly some fantastic advice that’s clearly referencing some of the discourse that’s growing in the community about how to make puzzles fun. I think a lot of DMs (and apparently game designers too) get hung upon on choosing or crafting their own perfect logic puzzle.

You want to make something challenging that will have your players scratching their heads, but jumping for joy when they solve it. You want to test their wits, their spatial or logical reasoning in much the same way you would if they were playing a video game or doing the New York Times Crossword.

This is a noble impulse but, ironically, it’s a trap.

Let’s talk about some of the functions of a puzzle according to Tasha’s Cauldron of Everything, which posits that we use puzzles for the following reasons:

- To encourage a party to discover information through teamwork

- To make a setting feel more whimsical, mysterious, or otherworldly

- To explain why no one has ever discovered something hidden close at hand

- To reveal a secret no one knows and magic can’t reveal

- To provide an opportunity for characters to use their skills in uncommon ways

Ok, these are pretty great. In particular, puzzles (and traps, actually) help tell the story of a place or group of people.

The Hovitos in Raiders of the Lost Ark must have loved their golden fertility idol very much to craft such a devious series of traps and a puzzle which, if answered incorrectly, would bury the idol forever beneath a mountain of stone.

This is all good advice for DMs looking to give their dungeons, ancient temples (of doom!), and royal treasure chambers a little more verisimilitude and flavor.

Even the point about characters getting to use skills in an uncommon way is good advice. Puzzles shouldn’t just feel like monster encounters by a different name or even a reworked social encounter.

If you’re going through the trouble to put puzzles into your game, then we might as well figure out what kind of experiences we want to create for our players.

Luckily, Tasha’s Cauldron of Everything is absolutely packed full of examples of what not to do. The puzzles it presents are, despite previous discussions about magic and whimsy, hardcore logic problems with fantasy tinsel draped over the top.

For example, the first puzzle presented in the list (which is graded as easy) uses a gallery of seven paintings, each one containing a different number of creatures (Gnolls, a werewolf, Dragons, and so on) as well as a conveniently placed riddle (virtually all the puzzles in this book use riddles to explain the rules, which is just so lazy) in the area reading…

“In order to gain all knowledge, one must know where to start. Count on your enemies to reveal the source of the secret. This room is dedicated to the defeat of all monsters within.”

The book suggests using it as the password to gain access to somewhere later, or having a giant stuffed owlbear in the next room with treasure hidden inside it! WHAT?!

Why would anyone (A) forget they put their treasure inside a giant freaking owlbear corpse? Or (B) feel the need to conceal that information with such a stodgy, needlessly obtuse logic puzzle.

You want to know what happens when you put that riddle in front of a bunch of actual D&D players?

- The players enter the room, ignoring the paintings and the plaque.

- They march right up to the stuffed owlbear because it’s the coolest thing in the room and either cut it open looking for treasure, or try to cast Raise Dead on it for a sick new mount.

- The players fight an undead owlbear.

- The players finally check out the plaque. They read the last sentence (“This room is dedicated to the defeat of all monsters within”) and assume this has something to do with monster feet (“de-feet – I get it!” screams the bard) and begin counting all the monster feet in the paintings and get into a huge argument over whether a gelatinous cube actually has feet or not.

- After ten minutes of this, the DM despairs and rolls for a random encounter. 1d4 + 2 guards show up and, in the confusion, the party’s rogue steals all the paintings.

The puzzles in Tasha’s Cauldron of Everything are all in this vein. They’re complex logic puzzles relying on handouts, a highly analytical party, and the assumption that there’s one correct answer.

Also, the RAW suggest that, if the players are struggling, they can make skill checks to get “clues” from the DM, which more often than not just give away how the puzzle works completely.

This means that puzzles go from being utterly inscrutable to solved with a single roll of a d20, which completely undermines the point of them.

As with traps, I think we can do better.

Three Tenets of Trap and Puzzle Design

Given the shortcomings in the RAW for both trap and puzzle design, we’ve come up with three key tenets that should, hopefully, solve these issues and create a more engaging, less frustrating experience for your players.

- Use Fluid Success States

- Make it Obvious

- No Meaningless Traps and Puzzles

Use Fluid Success States

This piece of advice comes largely from the Old School Renaissance (OSR) community, which is doing some genuinely fine work on the development of trap and puzzle design.

I’d advise checking out the OSR community on Reddit, as well as these posts by Goblin Punch and Into the Odd and Electric Bastionland creator Chris McDowall.

The basic suggestion is this: every trap should have multiple ways of disarming or avoiding it, and every puzzle should have multiple ways of solving it.

If you just want your players to lose hit points, throw a wandering monster at them. If you want your players to solve a logic puzzle with a single, narrowly defined answer, give them a bumper book of sudoku puzzles.

The goal of traps and puzzles is to put something in front of your party that feels different from other aspects of D&D – a game that’s all about infinite choice and possibility.

Consider all the ways in which an adventurer could have gotten past the light chamber trap in the temple in the opening of Raiders.

They could have dived through the beam, moving too fast for the spike wall to catch them; they could have picked up a massive shield and stepped into the light, hoping to absorb whatever danger came their way; they could have spotted a trap and investigated the side of the room to find the mechanism and disable it; they could trigger the trap with a thrown stick, an illusion, a darkness spell, or by just throwing a goblin prisoner ahead of them.

Some of those solutions require a skill check or saving throw, but some of them don’t. I’ve found that my players find it more satisfying when they solve a problem rather than letting their character do it with a die roll.

It’s the same with the pedestal puzzle later on. Let’s assume that – because we saw Indie fill up his bag of sand before he went inside the temple, that he already knew something about how the idol was protected.

As a DM, you could straight up tell a player that the platform detects changes in weight ahead of time (honestly, the odds that your players will completely forget this fact in the moment are solidly 50:50) or give them a cryptic clue.

Those who wish to leave burdened by gold must pay an equivalent exchange, or A hero may not leave heavier than they arrived.

Again, there are multiple ways that a player could solve this puzzle based on the information available: a bag of sand switched with the statue; leave a single gold coin in place of the idol (gold for gold); drench the pedestal in blood (“well it’s a fertility idol, so maybe we have to leave someone’s life force here in its place”) or replace the idol with a severed head.

No matter how obvious you think the solution to your puzzle is, your players are going to come up with something you never expected. And that’s ok.

Using fluid success states means, in essence, there’s no one right answer. There can be one best answer, but if your players come up with something unexpected that sounds plausible, let it work. They’ll feel clever and the story can move forward.

Likewise, if your players come up with an inventive, unexpected way of circumnavigating a trap, let it work, give them advantage, or otherwise reward their caution and creativity.

Make it Obvious

We’ve already established that traps in D&D often function like a tax. Roll a d20, if you roll low, a pendulum scythe swings down from the darkness and takes away some of your hit points.

Players might get to make a Perception check but, if they fail, the old hp tax can feel arbitrary and unavoidable. The only error the player made was rolling an 11 instead of a 12.

It can be the same with puzzles. You, as the DM, have unfettered access to all the knowledge within your world.

Your players, however, only have access to you. Dispensing information (how much, how often, in how much detail) is a common challenge to running D&D.

My take on the matter is that it’s always better to overshare. Give your players too little information – spring a scythe trap on them without any chance of avoiding it or coming up with a clever plan – and they’ll feel frustrated.

Give them all the information they need up front and you can sit back and watch them argue about the right way to proceed.

I’m not saying that you can’t hide nasty little surprises in your traps, or lay false leads and red herrings in your puzzles; that’s where a lot of the fun lies.

But the players should always feel as though they knew the risks, and that their injuries and failures are the faults of their bad ideas or calculated risks, and not the result of a lack of information and arbitrary mechanics.

The pit trap from Raiders is probably the most classic example of a trap that makes its presence obvious.

“A pit blocks the way forward. It’s 20ft across and descends down for at least 30ft to a bed of rusty spears. Above it, across the passage is a thick beam.”

The players now know the dimensions of the pit, the consequences of falling in and have access to a potential tool to make their way across. Of course, the players don’t know that the beam is only sturdy enough for one person to swing across safely, and the second person will need to make a Dexterity saving throw (DC12) to avoid falling back into the pit as the beam shifts and cracks.

The players could work that out, however, by pulling on a rope a few times, or making some kind of Intelligence check to assess its structural integrity.

Ben Milton, creator of Knave and Maze Rats, did a great video on using obvious traps that need to be disarmed through description rather than skill checks on his YouTube channel, which you should totally check out.

No Meaningless Traps and Puzzles

I was designing a dungeon recently for my weekly campaign. I put some gnolls guards on patrol near the entrance, stocked a room with some more gnolls, and drew a main room for a combination ogre boss fight/ritual sacrifice.

Then I noticed there was a hallway connecting the gnoll room with the boss fight and thought “well, I guess I’d better put a trap there.”

I put a pressure plate in the floor that triggered a volley of blow darts (that’s right, I never stop thinking about the opening scene from Raiders), put a few old darts embedded in the wall to make it obvious, and made a rough drawing of the mechanism that linked the pressure plate trigger to a set of spring-loaded bellows behind a false wall in case the players started asking awkward questions about how the trap worked.

My players made their way down the corridor, saw the darts in the wall, and our rogue said “don’t worry guys, the gnolls would have triggered any traps when they moved into this place”, walked forward, and took 2d8 piercing damage straight to the face.

Later, that rogue almost died because they were low on hit points during the boss fight.

My players griped to me later about this, and I’m here to tell you what the experience taught me: no trap is better than a trap that makes no sense.

Just like finding an ancient red dragon in a room with one human-sized door, a trap where it makes no sense for a trap to be can be a huge immersion-breaker for your players.

This excellent video by Dael Kingsmill expands further on the idea of traps and puzzles that make sense within your world. I highly recommend it.

Traps and puzzles exist in your world for a reason. Somebody built them. Somebody might still maintain them. And (if they exist within a place that’s still in use) there are probably ways that people regularly bypass them.

It might seem like I’m making the process of putting traps and puzzles in your game even more daunting than it already is, but making traps and puzzles make sense is also a great opportunity to show your players a richer, more interesting world than they otherwise would experience.

I could have very easily fixed my gnoll temple dart trap, for example, by adding a few markings in the gnoll language reminding gnolls who come this way not to step on the pressure plate.

This could actually have spiced up the fight in the previous room as well if, as the last few gnolls felt the tide of battle turn against them, they had fled down this passageway, trying to lure the players into their dart trap.

It’s the same with puzzles.

Whoever made this puzzle either intended for it to function as an elaborate lock that they (or someone else) might return through someday, or as some kind of test to determine the worthiness of a stranger looking to pass through.

If they never wanted whatever’s behind the puzzle to be found, then why not just build a big wall?

Puzzles and traps for the sake of puzzles and traps can erode the verisimilitude and fun of your game, so it’s always worth putting at least some thought into the purpose they serve beyond a break from combat for your adventurers; D&D’s classic excuse of “I dunno, a wizard made it… a maaaad wizard!” doesn’t really hold hydrochloric acid anymore.

Bonus Tip: Make it Weird

Because there aren’t really any rules for traps and puzzles (no good ones at least), you’re left free to get as weird with them as you like.

There’s nothing that says traps can’t have insanely strange magical effects or be incredibly complex Rube Goldberg machines, force players to automatically fail their saving throws, or break the laws of time, space and physics just a little bit.

Be creative, be weird, step outside the framework of D&D’s mechanics in ways that bring your players with you on a weird, boutique journey.

Bonus Bonus Tip: Add a Ticking Clock

Because there’s only one of you and usually between three and five players, you’re probably not going to be able to outsmart them in a vacuum.

As the hydra proves beyond a shadow of a doubt, multiple heads are better than one.

Also, momentum in D&D is actually a pretty tricky thing to preserve. Players tend to hyperfixate on irrelevant details, or talk one another round in circles for hours.

One of the best ways to light a fire under your players’ butts is to, well, literally light a fire under their butts. Set the room on fire.

Even the most deliberative player is going to start trying stuff as they take a d4 of fire damage on turn one, a d6 on turn two, then a d8, and so on.

Or you can have the room start to fill with water, or poison gas, or bears. Or give the players a narrow window to crack the safe before the next guard patrol comes through, or the wizard whose tower the players are robbing comes home.

Adding another element – be it an environmental threat, a secondary trap, or a monster – can really ratchet up the tension, force your players to make quick decisions, and ultimately make for a more memorable encounter. Few D&D anecdotes begin with “hey, remember that time we spent four hours staring at that door? Good times.”

A Trove of Traps

Below, we’ve put together a collection of devilish and dangerous traps that usually intersect with at least one of the core tenets of trap design described above. You’ll note that these entries aren’t stat blocks, and only a few of them have specific instructions for things like damage and saving throws.

This is because they’re intended to serve as a universal template of trap that you can add to your game with minor adjustment; they’re intended to be setting and theme agnostic.

The Obvious Pit Trap

The classic pit trap. The way is blocked by a 30ft deep pit that is too wide to jump (about 21ft should put it out of range for all but the most athletic adventurers). Adventurers who fall into the pit take 3d6 bludgeoning damage from the fall and an additional 2d8 piercing damage from the rusty spear tips that line the bottom of the hole.

This trap is all about keeping it simple and letting your players get creative. Maybe they’ll try and construct a bridge using a tree from outside the dungeon, or the wizard could open a portal to the plane of water so the pit fills up and they can swim across.

Evil Twist: the floor 10ft beyond the far edge of the trap is illusory, and contains more empty space above spikes. Make sure you hint at this to the players by describing the floor beyond the pit as much cleaner than the rest of the dungeon floor, or they can use detect magic, or even a skill check.

Fire in the Hole

This trap comes from the Crypt of the Science Wizard by Skeeter Green Productions. The adventurers come across a yawning pit that’s too deep to see the bottom. From the pit also emanates the smell of some pungent chemical mixed with lamp oil.

The pit is bridged by a balance beam, wide enough for players to cross with a DC10 Dexterity check.

However, the post supporting the middle of the beam is on a swivel; any weight placed upon it causes the beam to tilt and anyone standing on it to drop into the pit. You should make this obvious to any player who doesn’t immediately try to walk across.

There’s another layer to this trap: the swivel mechanism comprises two plates which rub together when the beam turns. When this happens, the plates grind against one another and send a shower of sparks down into the darkness below, which is full of combustible oil and fumes. A huge tongue of flame shoots up and immolates the poor adventurer on their way down.

If the shower of sparks is big enough to light the fuel below, characters caught on the bridge in this inferno suffer 24 (7d6) fire damage and gain 2 levels of exhaustion if they don’t get off the bridge in a hurry, then take 63 (18d6) fire damage and suffer 2 additional levels of exhaustion if they linger, and are finally utterly incinerated.

The Sticky, Stabby Situation

This trap comes from the Book of Challenges for 3rd Edition and I’ve taken the liberty of tweaking it for 5e with some of the suggestions from Matt Colville’s video on traps. It has multiple stages and features everyone’s favorite low-level monster, the Gelatinous Cube.

The players walk along a hallway that ends up ahead in a T-junction. The trap is sprung by a pressure plate on the floor (DC 16 Perception to spot) which releases a portcullis that falls in the middle of the party, cutting the adventurer who triggered the trap off from the rest of the party. The trapped adventurer can go left or right, but not back the way they came.

Now, here’s where things get evil.

Down the left-hand passage of the T-junction is a large, obvious lever that the player should be able to see from far away. They will likely assume that the lever raises the gate.

However, they are less likely to notice the Gelatinous Cube occupying this same space; it’s transparent, so the player can see the lever through it. While their allies panic, the adventurer extricates themself from the cube and, likely also panicking, runs right down the other passage where there’s a door.

This is a false door. Turning the handle opens a pit trap underneath the player, dropping them onto a pile of spikes. Then, while they lie there at the bottom of the pit, the Gelatinous Cube appears at the top of the pit and schlorps down on top of them. Brutal, cruel, hilarious.

The Bear Trap

This one you have to drop hints about ahead of time. When your players ask locals about the nearby dungeon, the locals need to shiver in fear and say things like “no one ever comes out alive. It’s full of bear traps.”

Have a local retired adventurer with a missing foot talk about how dangerous the bear traps in the dungeon are. Really drop as many hints as you can that misdirect the players into thinking that there are a bunch of bear traps littering this place. This shouldn’t freak them out, and they’ll figure that, as long as they proceed with caution, everything will be fine.

Somewhere in the dungeon (which is suspiciously free of bear traps – something that will probably be starting to freak your players out a little by this point) the players should enter a room with some sort of trigger. You can use a pressure plate, a weight-sensing platform, even a tripwire.

Either way, it should be loosely linked by a piece of string to a single rusted, almost-broken bear trap. What the players will only notice if they examine the bear trap is that there’s another piece of string running from the trap up into the darkness above.

The overconfident players will trigger the bear trap, which in turn will trigger a door in the roof that opens and drops a live, angry bear on top of them.

Evil Twist: Have the “bear trap” open and drop a bunch of bear bones on the adventurers. They take no damage but it’s super sad. Then, have the bear bones animate and attack the party for some added nightmare fuel. Or have the party be hunted later on by vengeful ghost bears. Yeah, that would be even worse.

Hall of Blades

This trap is meant to provide an alternative to the deeply unsatisfying “roll perception, roll dexterity… a scythe swings out of the wall and hits you for 1d6 slashing damage” type of damage tax trap.

Instead of hidden blades, just fill an entire corridor with constantly spinning knives, axes, flywheels sharpened to a point, and any other kind of unpleasantly sharp thing you care to imagine.

They’re all being powered by something in a nearby room (maybe even something you can see on the other side of the blades), but the players need to get through this hallway anyway. Just like the Obvious Pit Trap, this is a trap you can just drop in front of your players and watch them get creative.

Evil Twist: The blades are illusory.

Portcullis Trap – Divide and Conquer

An element of this trap is present in the Sticky, Stabby Situation but you can use this anywhere. Use a pressure plate or tripwire to trigger a portcullis (they’re better than doors because the party can still see and hear one another) that drops, splitting the party.

The portcullis can be lifted up far enough for someone to squeeze under with a sufficiently good strength check, but your players may not have time for that. When the portcullis comes down, the noise alerts some monsters or guards in the next room, forcing half of the party to meet this new threat while their allies can only watch, maybe shooting off a few spells or arrows in support.

Evil Twist: After a few rounds of combat, more enemies arrive from behind the party, attacking them on two fronts. This is particularly useful if your players pay attention to their marching order, putting the paladin and the fighter in front with the squishy wizards in the back.

Mosaic Floor with Poison Darts

Present a room with a mosaic-covered floor containing the designs of several animals: clown fish, puffer fish, sharks, puffins, and barracuda. You can change these creatures to match the theme of your dungeon, but one of them should be highly toxic or poisonous, one should be immune or resistant to poison, and the rest should be more or less harmless.

The animals are arranged in a repeating pattern. Stepping on an image of a puffer fish triggers a hail of darts that hit everyone in the room except someone standing on a clown fish tile.

You can also fill this room with a bunch of red herrings, like tripwires connected to nothing, shafts of light, statues with eye lasers, whatever you like.

Make it very clear to your players that something in this room causes volleys of poison darts and watch them poke this room in fear. Depending on how badly the player walks into the volley of darts, for every dart that hits them (if they’re being careful, hit them with 1d4 darts, and make the die bigger if they’re somehow beefed things up even worse) for 1d4 piercing damage, followed by a DC12 Constitution save or take 1d6 poison damage.

Evil Twist: You can also release something small but irritating into the room each time the players mess with something that’s not the mosaic floor, like a swarm of bats, rats, or insects. Before long, someone in the party is going to get fed up and just walk through the room, with hilarious consequences.

The Faerie Ring

This trap comes from the community post of 1d124 OSR-Style Challenges by Goblin Punch.

There’s a circle of mushrooms with a girl inside it. Everything inside the circle of mushrooms will do everything in their power to get more people inside the circle (no save). The girl is already their thrall.

What happens to someone who spends a night in the circle, or how people react when forcibly removed from the circle, or how effective it is when your players dig up the mushrooms and plant them again somewhere else, is entirely up to you.

Orb of Snakes

Another excellent and obvious trap from the Goblin Punch community.

This glass sphere (3′ in diameter) is filled with gems and horrible undead snakes. You can play around with this concept however you like, but the function is always to put something very obviously dangerous in immediate contact with the treasure. How will your players open the orb safely? Just how deadly are the undead snakes?

On top of the mechanical danger, if the image of a small glass orb packed with brightly colored gemstones and dozens of necrotic, writhing snake flesh doesn’t seriously freak your players out I will eat a hatful of snakes.

The Rope Trick

This is essentially an evil twist on the pit trap. There is a large hole in the floor blocking the way forward. Hanging from the ceiling in the middle of the pit is a rope, the end of which is tied up somewhere the players can reach.

Your players might assume that the rope is there to swing across the pit and, if they pull on the rope a little, it will appear to be safely secured. However, if more than 100 lbs of weight is placed on the rope, it will begin to rapidly unspool from a hidden chamber above the ceiling. The hapless adventurer is then lowered at speed into the pit below.

You should make it clear that the bottom of the pit is strewn with victims. It’s fair game to let your players know this pit trap regularly kills adventurers. You can fill it with blood-soaked spikes, ravenous Black Puddings, or a bath of acid and bones.

Evil Twist: A player who is dropped into the pit on the now much longer rope may assume that, if they pull the rest of the rope out of the ceiling, it will stop unspooling and allow them to climb up. When the rope reaches its end (after another 50ft is pulled out) you hear a ‘Click’ and the ceiling collapses into the pit for added insult to injury.

Rolling Boulder Hallway

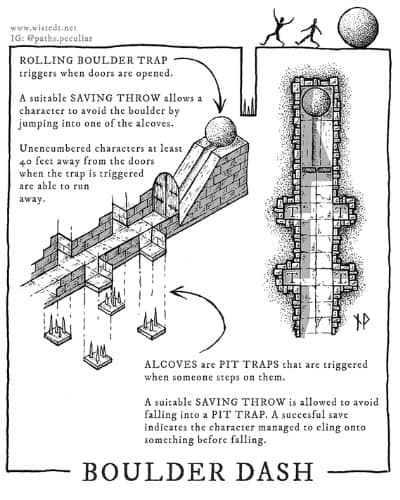

This riff on the classic trap from Raiders comes from Paths Peculiar on Instagram.

The players find themselves in a long hallway with several small alcoves along each side (ideally one fewer than there are people in the party, if you’re feeling cruel, although you can roll a d4 +1 if you want to absolve yourself of some of the responsibility) and a large set of double doors.

The corridor slopes upwards at a 10-degree angle leading to the door which leads to a much steeper slope, at the top of which is – you guessed it – a rolling boulder. Opening the door releases the boulder, giving the players a few seconds to either try to run down the hallway, hide in the alcoves, or take a life-threatening amount of bludgeoning damage.

What the players probably haven’t realized is that the alcoves all have false floors that trigger under enough weight, dropping the players into… well, you decide. Are they now at the bottom of their own incredibly narrow shaft? Have they all been dropped into the same pitch-black, monster-filled lake? Is it perfectly safe?

You should hint at the presence of a room underneath the hallway. If it’s full of water, you can use the sound; if it’s full of corpses, use the smell.

The Short Straw Spike Trap

This trap adds an extra layer of challenge to the classic descending ceiling trap room from Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom. A pressure plate or tripwire that shuts the doors in and out of the room, and the ceiling begins to lower inexorably onto the players.

The room contains a number of depressions in the floor, each of which is big enough for a single medium humanoid to hide in. The number of depressions should be one fewer than the number of people trapped in the room, meaning that all but one adventurer can safely wait out the trap, and that the party must quickly decide who’s getting squashed.

The Doppeldoor

Lastly, we have a strange one that requires you to work a little with one of your players. This trap takes the form of a door. As soon as someone steps through it, they are instantly transported to a pocket dimension.

A doppelganger of them is sent back through the door a few seconds later. It can be fun to have the now trapped player roleplay their doppelganger, who is now devoted to undermining and ultimately killing the party – or perhaps convincing the other players to go through the door themselves.

A Pile of Puzzles

The Way Too Obvious Pit Trap

Exactly the same as the Obvious Pit Trap from the section before, but even deeper. Make it look really menacing – lining the bottom with skulls, or covering the walls in scratch marks and dried blood.

A cunning player should be able to tell, however, that the blood is actually coagulated beet juice, and the scratch marks were made with a sword on purpose.

There is a trapdoor at the bottom of the pit that leads to where the players want to go. Hint at this with a gentle breeze rising from the pit to indicate it’s not a dead end, but otherwise let the players make their way across.

If you’re feeling generous, include an obvious switch at the bottom of the trap that causes a ladder to extend from the wall, allowing easy access.

Sun/Moon Door

A door covered in engravings, or a riddle (“Beneath the earth I remain, forever closed, for the celestial key of day/night’s glow” – or something to this effect) that can only be opened in direct sun or moonlight.

The catch? It’s at least a few floors underground, meaning the players will have to find a creative way of getting the light down here. I’ve seen solutions to this puzzle ranging from an intricate array of mirrors to hiring several hundred local peasants to excavate the entire first level of the dungeon.

Infinite Stairs

A magical spiral staircase. At the top: a riddle (you can also seed this earlier on).

“If into light you wish to tread, into the dark you must go instead.”

Players who start walking down these stairs while shedding any light at all become trapped in an endless loop as a transportation spell continues to send them back to the top (the door has disappeared) over and over again. The stairs only allow people to exit at the bottom or top that descend far enough in total darkness.

The Cup of Destiny

An open-ended puzzle that involves an elaborate cup, font or basin that can do any number of things, from opening the next door to laying all nearby undead to rest.

The cup is empty and must be filled with some sort of substance… and that’s it. Sit back and let your players experiment with wild theories and speculate their way to a solution. When they come up with something that sounds plausible, let it work.

Evil Twist: More cups that have different interactions and effects depending on which one you drink from and what you drink from it, from being able to fly to bestowing curses.

Every time the players turn their backs on the pile of cups, more of them appear, each with a unique effect. It’s an infinite and potentially frustrating toolbox for the party to experiment with and be confounded by. Also, the door they’re trying to open has been unlocked the whole time.

Acid Pool

A deep pool of powerful, clear acid with the key to the next door or some treasure at the bottom of it. Anything organic submerged in the acid is rapidly dissolved (players take 2d6 acid damage on the first turn, then 3d8, then 4d10, and so on.

Difference Mirror

The players find themselves in a room full of junk and strange items (shrunken heads, bronze statuettes, oil paintings, etc.) with a huge mirror at one end. Perceptive players will notice that one item from the room is reflected in the wrong part of the mirror.

If they place it in the right part of the room, the players are transported into the mirror with a faint popping sound. The door they came in through now leads somewhere else.

Choose Wisely

This one is straight out of Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade. A room containing a font of water and, like, 200 cups of different styles, sizes and materials.

One cup is genuine and has healing powers, or grants eternal life. All the other cups inflict something really nasty, like 10d12 poison damage, four levels of exhaustion, petrification, or the true polymorph spell (into a cup for added injury).

You should seed the preceding dungeon space with information about the owner of the cup. Maybe a sea elf wizard with a nautically themed dungeon might have a cup encrusted with seashells.

Frictionless Wall

A 100ft high wall with a door and a ledge at the top. The wall is completely frictionless, making it virtually impossible to climb or descend safely.

This is another one of those challenges with no moving parts and no clear answer; it encourages players to get creative. This puzzle works well in the lair of something with magical powers and the ability to fly. Dragons, beholders, and mad mages all apply.

Common Questions About 5e Puzzles & Traps

How do traps work in D&D?

Traps in the rules as written usually require a perception check to spot (the DM can also use the players’ passive perception to calculate the result in secret), a saving throw to avoid or mitigate their effects and, if that roll fails, the DM inflicts some sort of damage, or otherwise incapacitates or inconveniences the player.

What’s the difference between traps and puzzles?

The difference lies both in the intent behind their construction, but also in the fact that usually, (not always) puzzles are something the players can engage with voluntarily.

A puzzle exists to be solved in order to gain access to new rooms, treasure, or something else the party needs. Traps, on the other hand, are imposed upon the party, or used to deter them from entering an area.

What skills let me find and disarm traps?

Any skill, creatively applied, could be used to disarm or spot a trap – there are just so many different varieties of trap to find and deactivate.

However, the most common skills used for finding traps are Perception and Investigation.

Where magical traps are concerned, the DM might call for an Arcana roll. When disarming traps, the DM can commonly call for a Sleight of Hand check. When a trap is triggered, Acrobatics is a common saving throw.

I played my first tabletop RPG (Pathfinder 1e, specifically) in college. I rocked up late to the first session with an unread rulebook and a human bard called Nick Jugger. It was a rocky start but I had a blast and now, the better part of a decade later, I play, write, and write about tabletop RPGs (mostly 5e, but also PBtA, Forged in the Dark and OSR) games for a living, which is wild.